What’s wrong with classical music?

The research context for ‘Dido & Belinda’

By Daniel Leech-Wilkinson

As part of King’s College London’s Arts & Humanities Festival 2016 (for which the overall theme was PLAY), the young opera company Helios Collective, their artistic director Ella Marchment, conductor Leo Geyer, and a cast of young professional opera singers and players, staged a ‘Dido & Aeneas’ that departed in many ways from what’s currently the standard version. I choose my words carefully here—not ‘Purcell’s version’ or (most misleading of all) ‘the original’—although it very often is the original that we suppose we’re getting when we go to a modern performance. We’ve become used to assume that when original instruments and carefully edited scores are being used we are somehow getting the original musical interpretation, or at least the original performance style and sounds.

Let me show why I don’t think it is remotely like any ca 1700 original by providing an example of Mozart. I’m using Mozart because the demonstration requires early recordings, and there are no very early recordings of Purcell. So here is the first phrase of the second movement of Mozart’s ‘Coronation’ concerto, recorded by pianist (and composer and conductor) Carl Reinecke in 1905. Reinecke uses dislocation of the hands (he rarely plays all the notes of a chord together), uses inégalité (he turns regularly notated rhythms into irregular sounding ones), melodic decoration and rubato (he varies the length of the beat), only one of which (melodic decoration) would be acceptable in a modern performance (and then only in a ‘historically informed’ one).

Carl Reinecke: Mozart, Piano concerto no. 26 in D K.537, 2nd mvt, opening (recorded 1905) [Click on the left-hand end of the black bar if there’s no PLAY button]

Why should this performance matter to us? Because Reinecke was born in 1824, the year Beethoven’s 9th Symphony was first heard. Apart from that melodic decoration, none of this belongs to current ‘historical’ (or non-historical) Mozart playing, because no one at the moment can believe that Mozart could ever have sounded like that. But it did; at least when played by a very long-lived pianist in 1905, and very probably by that same pianist many decades earlier, perhaps as early as ca 1840 when as a young performer he was establishing his way of being musical, in relation to the performance style current around him. How much of this goes back to the end of the 18th century we cannot know; but it is certainly much closer to Mozart than we are.

What this huge distance in musicianship shows us is not how Mozart sounded to his contemporaries; rather it shows us just how many other ways there must be, than we have ever heard, of playing the same notes. And this is actually much more important. We must assume we don’t know and never shall know how Mozart’s performances sounded. This isn’t just a matter of which instruments were used and which notes were played. Every tiny detail of a performance affects the character of the sound and interpretation. And none of that can be described in words that can survive from one generation to another, nor does it emerge intact from using the same instruments. It’s lost, forever. We may stumble across it again by chance, but we shall never know that we have, and if we do it will soon be gone again as performance style continues to change, as it always inevitably does.

And so, when it comes to performing scores, whatever we may intend to do and however we wrap it up with justifications of various kinds, in practice we take the notes in the score and we make the music we like with them. Recordings show that what we like changes all the time.

*

‘Dido’ is opera, so let’s look next at a vocal example. Here is the first phrase from Schubert’s ‘An die Musik’, a homage to music in which singers get to tell us about their deepest feelings for the art. To a modern singer this is a relatively straightforward song, with even-length notes sung over a very regular piano accompaniment. But this is how it sounded in 1911:

Elena Gerhardt, acc. Arthur Nikisch: Schubert, ‘An die Musik’ (recorded 1911 on HMV 043202 ac5112f, transferred for the author by Roger Beardsley)

Many today can’t see how that could ever have been thought musical, let alone ideal. But it was. Elena Gerhardt was one of the most famous and admired singers of her day, and her accompanist was one of the leading conductors, Artur Nikisch. This was Schubert 100 years ago: in 1911 Schubert was this composer. Since then he has changed a very great deal. And presumably he changed a very great deal to become the Schubert of 1911. But we cannot sensibly assume that our age has found the historical Schubert once more. How could we? Why should we imagine we have? Except that we, like every generation including Gerhardt’s, simply assume that, because the way we sing and play makes perfect sense to us, therefore we have at last got Schubert right, and that everyone before us was simply wrong.

So humility as to what is historical and unhistorical is required of us. And that already offers a huge challenge to the basic ideology of classical music practice.

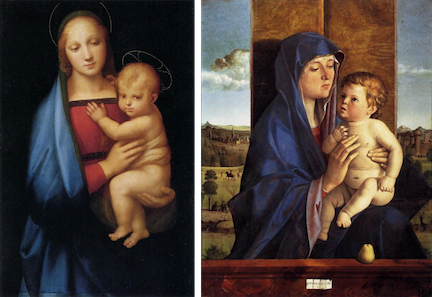

Let’s ask the same question of painting.

You may say this is the wrong comparison, that I should be comparing compositions with paintings, not performances of compositions, but actually the paintings are performances of Virgin-and-Child with its associated iconography, which is entirely comparable with what’s in a composer’s score: they’re two renditions of the same moderately detailed instructions.

If this were two musical performances you can easily see how anyone who believed one was correct (in its use of the colours, the clothing and the positions of the bodies) could be outraged by those details in the other. “The veil covers her forehead, you can see the lining of her sleeve, her mouth is almost touching the infant’s hair. This is disgraceful, it wilfully misrepresents the church’s intentions”, and so on. And someone ca 1500 might have thought that. But in art criticism we’ve got over that now; we don’t require our aesthetic responses to be determined by what’s doctrinally correct, let alone what was doctrinally correct in 1500. But in music criticism we’ve not grown out of that, as yet. Our aesthetic responses are rigidly ruled by which we think is the more ‘correct’. If the one on the left, then the one on the right is “self-indulgent, deliberately perverse, a travesty of the church’s intentions”, and so on. And this is the kind of language you read in reviews of musical performances all the time.

About the pianist Artur Rubinstein: ‘timeless Chopin, cleansed of self-serving idiosyncrasy and preening mannerisms,’ Gramophone magazine, Awards issue, 1999

(Note the word ‘cleansed’, as if other performances were dirty with performer interpretation.)

About pianist Adam Harasiewicz: ‘not for those who warm to Chopin plastered with self-serving idiosyncrasy’ Gramophone, February 2011

(Plastered, self-serving, idiosyncracy, as if the performer were only playing Chopin in order to glorify himself, covering it over with his personality, claiming it as his.)

About pianist Christoph von Eschenbach: ‘the playing is accomplished and showy, but its beauty is entirely cosmetic, like a reflection of Eschenbach’s own narcissism’ Gramophone, August 2007

(How many of us would write that about a performer for publication? Or even think it?)

What is going on here? Why are critics so nasty about performers: performers, let’s remember, at the very highest level of accomplishment? What has upset them so much that they feel comfortable to write in these terms? What has happened here? Only that the reviewer noticed something was different, didn’t like it being different, and wants to stop it, by being so unpleasant and so personal that the player never risks it again. It’s all about policing difference, promoting conformity. Is that what we require of classical music performance, and if we do, is there something wrong with us rather than with the performances?

We practise homogenised, unchallenging classical music as a kind of Utopia, a sort of post-Brexit Albion, a perfect society, walled off from the rest of the world, which it would be unforgivable to disrupt. Music will produce Utopian experiences, we believe, provided that we follow the composer’s commands. The composer is the beloved leader in this ideal society whom—if we want to produce ideal results—we must always obey. But in truth he is no more than a front for all the rules and obligations through which order is maintained. Utopias are inherently totalitarian: everyone has to follow the rules. And it’s exactly that uniformity of behaviour and belief that we’ve just seen these reviewers trying to impose (one hopes without any idea of what their words imply).

At first this isn’t a problem. The young musician accepts their teacher’s word, learns the fundamental rule: ‘play what the composer says, get praise’. (Though of course what that really means is, ‘play what teacher says, get praise.’) Young musicians feel they’re being creative as they learn the moves their body needs to make to sound acceptably expressive: as the moves start to work they’re happy to accept the beloved leader as the source of their delight.

But norms are of course oppressive, and as the student learns to behave within them they are also aware of gradually increasing fear: fear of making a mistake, fear of playing out of style, fear of non-conforming, of being judged unsuitable for work, of being judged ‘unmusical’.

This is brilliantly, if unintentionally encapsulated in the trailer for the 2013 B-movie ‘Grand Piano’: a concerto soloist turns the page to see scrawled on this score, ‘Play one wrong note and you die’:

‘Grand Piano’, dir. Eugenio Mira, 2013: trailer

For many performers, that’s exactly what it feels like to go on stage and face the critics.

So, with increasing technical and stylistic demands comes fear. With fear comes stress, anxiety, and performance-related illness, a plague now for which the ideology is substantially responsible. The performance police are everywhere. Teachers, examiners, adjudicators, agents, critics, promoters, producers, record reviewers, bloggers. Performance is policed from first lesson to farewell recital.

Musicology also has a lot to answer for, with its claims to be able to discover what the composer wanted. And so the performer is persuaded that their job is to manufacture the composer’s wish. The critic purports to represent the composer’s best interest, and claims they have a duty to enforce it. At the end of the chain, the listener pays for it all by buying the tickets along with the ideology.

Lisa McCormick, Performing Civility: International Competitions in Classical Music (Cambridge, 2015)

As Lisa McCormick reveals in her recent book on music competitions, on the one hand jurors, agents, and programmers will all tell you they are looking for a performer who has something unique to say, while on the other all their values in relation to composer, score and performance tradition, tend towards enforcing conformity. The competition between performers is thus to conform more strikingly, more persuasively, to be a better cheerleader for the system. Thus whenever a performer risks playing significantly differently—and it doesn’t happen often—you can be sure there’ll be a critic there ready to denounce them for narcissism and self-indulgence.

These writers, parroting this fearful phrase, belong to an army of gatekeepers who police performers to ensure that their playing conforms to the State’s norms of virtuous behaviour. The gatekeepers’ sense of their own loyalty to the imagined, beloved composer, drives their urge to enforce rules – social, moral, stylistic rules. And those rules tend to conflate, into one overarching law, the two key requirements of approved performance: to be perfect in execution and to be perfectly faithful to the imagined composer. Runaway selection then ensures that ever higher performance-display, and ever more faithful representation of the imagined composer’s imagined wishes, spiral in an apparently unstoppable inflation, because they offer performers the only remaining route to ‘outstanding’ success, the only legal way of being different from all the others.

Izabela Wagner, Producing Excellence: The Making of Virtuosos (Rutgers University Press, 2015)

There is a persuasive view of how virtuosos are made in this recent book by Izabela Wagner.[1] Wagner was a parent of a child violinist being prepared for a career as a virtuoso. But she’s also a sociologist. So she was able to use her insider access to the rarified world of the international virtuoso class and the competition circuit to write a close-up study, that a sociologist who observed only as an outsider could never have achieved. She doesn’t, I think, set out intending to reveal that world as corrupt, nepotistic, dishonest, ruthless, cruel, above all self-sustaining. But simply reporting what she sees and hears inevitably leads the reader to that conclusion.

We see how parents, with the best of intentions, conspire with teachers, silently looking on as teachers bully and threaten young children to practice to the exclusion of all else, to forego other education, to obey their teacher without complaint, as far as possible without contributing anything of themselves at all. Through routine, children become willing slaves, hoodwinked, like their parents, into believing that if they do exactly as they are told by their teacher they will become the next Heifetz. Wagner shows how teachers on the virtuoso circuit promote the idea that only they can lead a child to international stardom. She exposes the way in which students who leave a teacher, or who are expelled for being insufficiently obedient, are never spoken of again, so maintaining the illusion that all the teacher’s students will succeed, alongside secret fear, among those remaining, of stepping out of line.

She shows also how the teacher and student become mutually dependent: the teacher needs the student to preserve, perform and pass on their own approach to technique and interpretation, so that the teacher’s memes are reproduced; while the student needs the teacher’s support to make contacts, win competitions, get work. She shows how teachers actively intervene to prevent people who challenge them getting gigs. She reveals the extent of corruption in competition judging, the promotion of the judges’ students, the bending or ignoring of the rules to produce a result that promotes the judges’ interests, the way in which judges and organisers interchange from one competition to another. Above all, in the ways in which untruths are promoted and repeated in order to maintain the effectiveness of these teachers’ grip on power, the world Wagner describes corresponds exactly to the police state I’ve just described.

This should come as no surprise. Police states aspire to the condition of Utopias, and Utopias are necessarily police states. But actually, why on earth do we need a police state for classical music?

Theatre isn’t nearly this restrictive. It’s perfectly normal to perform Shakespeare in search of new meanings that tell us something about our situation today. The idea that an actor is obliged, in order to get work, to perform a play according to Shakespeare’s intentions is comical, insulting even, because we know that actors can do so many differently persuasive things with the same text. Occasionally it’s interesting to hear an attempt at Shakespearean theatre, but few people think there’s a moral obligation there, or that the text won’t be Shakespeare, or will be outrageously misrepresented, if it’s interpreted differently.

In the visual arts, the idea that one is obliged to as far as possible reproduce tradition seems completely mad.

So what makes us behave so utterly differently when we perform classical music? What makes it professionally impossible for the Royal Opera House to perform Mozart as creatively in the pit as it does on stage (below, Cosi fan Tutte), something which seems on the face of it so thoroughly hypocritical? This is the issue we’re trying to address with our reimagining of Dido & Aeneas, as Dido &… Belinda.

But before we go there, how should we rethink our attitude to the composer’s intentions? I’ve already shown how this is a problem peculiar to classical music. No one else thinks they have to obey someone who’s been dead for centuries, except of course… the religious. And you can see how treating music as a Utopia, in which doing exactly what the score says (and what our gatekeepers tell us the composer wanted) is the only route to the perfect performance, is a form of religious observance, with all the peculiarities and shortcomings of any belief system.

Let’s instead try to think afresh about what we might ethically owe a composer.

First of all let’s consider living composers. Composers are imaginative musicians. They imagine music, and notate what they can. As they notate, they imagine their scores played by performers they know or have heard. So, if they’re writing conventional scores, they have expectations. As first performers of their scores, I think we’re all interested in hearing what they imagined. Or we are if we have any respect for them as imaginative musicians.

But in any case, it seems a simple courtesy to living composers to try to make the sounds they had in mind. When someone gives you a score on which they’re worked hard, and offers you the chance to play it before anyone else, the least you can do, out of politeness and respect, is to try to give them a performance of what they’ve imagined. I think that’s a basic obligation of courtesy.

Of course, you may do some things, perhaps many things, that they’d not expected. And usually composers are delighted when that happens and willingly accept your view of their score. I think it’s important to remember that, when we come to think about dead composers. But the main point is that the composer is there, they can be consulted, you can work with them, and in the end you represent them to a wider audience. And all this brings some obligation to please them as well as your listeners. Because this is a human relationship, in which, as in any humane relationship, you try not to hurt their feelings; ideally, you try to give them pleasure, to make them happier. That’s what we do for one another when we interact on equal and friendly terms.

But how much of this applies in the same way when the composer is dead? When they’ve recently died, then there are many friends and admirers, and family, who remember them and thinking lovingly of them. And to the extent that that is maintained or enhanced or fed by the way you play their scores, then I think there remains an obligation to play scores in ways that please survivors. It’s exactly as one would not speak critically of the dead to those who knew and loved them. But as time passes, this obligation diminishes. Their closest friends and family die too, and there is less and less need, out of human kindness, to play scores in the same way as before. And more and more opportunity, therefore, to see what else those scores can do. And this is exciting. It’s an opening up of possibilities, as time passes, to explore scores in search of new meanings, meanings that perhaps are more interesting and relevant and revealing for new generations. That, too, seems to be an ethical obligation to the living; to make scores sound relevant and revealing.

What is absolutely clear—unless one believes that the dead are alive, and have nowhere else to be—is that dead composers are not harmed by performances of their scores that they might not have liked. And once nobody else is harmed (and I mean harmed, not offended: of course art must be allowed to offend, and it’s high time classical music audiences got used to that idea); once nobody else is harmed, there is no ethical obligation at all to continue to perform in the original manner. We’ve seen that new kinds of performances are possible, and that they emerge over time in any case. But what I am arguing, and I think on strong ethical grounds, is that new performances can and should be deliberately made. Because scores can mean so many different things, because performers can be so innovative in persuasive ways, because the results can offer audiences new kinds of musical experiences from scores rich in potential, because performers and audiences can find delight in unexpected insights, in being creative and in experiencing creativity, because innovation offers a reason to go to concerts, to make and buy new recordings, to maintain a healthy economy of musical performance that keeps classical music lively and rewarding, financially and spiritually; for all these reasons, allowing performers to imagine and play scores differently is not just desirable, it is the right thing to do. And that makes it our obligation.

*

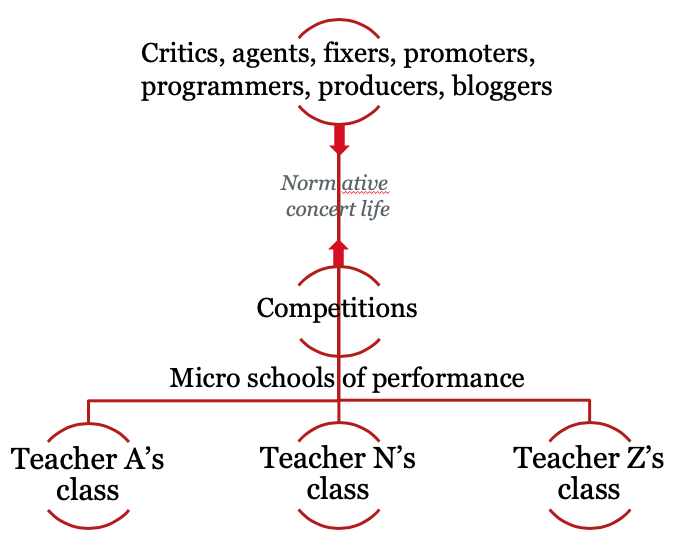

So, why is the music business so ruthlessly and resolutely opposed to substantial performer creativity or innovation? The reasons, as ever, include power, and money. I’ve already suggested, and Izabela Wagner has implicitly shown, that music education is designed to ensure that the most brilliant performers perform existing normative readings of scores. The whole purpose of the system is to control performance interpretation, and to constrain it within the narrowest possible bounds. Performers, as I have said, win competitions and get the best gigs, by performing the norm more persuasively than anyone else. By the time they are renowned enough to do what they like, without losing their audience or losing work, they are so invested in their superlative normative readings that there is no incentive to innovate. Why would they? The norm is part of their embodied musicality, part of the way their body and brain have learned to be musical. Significant change is far too challenging to contemplate. The slightly less successful performers are teaching the next generation, and their interest is in passing on themselves to students who may, through their own success as soloists, be able to pass those teachers’ memes back into public consciousness.

Cultural power, then, depends on passing on very slightly personalised norms. Each teacher, each soloist, is slightly different, enough for specialists to recognise, enough for them to feel they have something of themselves to reproduce in the next generation. But not enough for any rival to be able to accuse them of betraying the norm. There is rivalry, of course, enough to keep teachers’ pupils loyal, enough to see other teachers’ classes as Other, but not enough for critics or similarly ideologically invested audiences to see any one of these micro-schools of playing as deviant, rather than as fractionally (and to the specialist, interestingly) different.

The pressures on performers to conform

Those are all aspects of power. What about money? First, of course, the money men—the agents, critics, promoters, fixers—have to work with the products of the conservatories and the virtuoso classes. They are just as invested as the teachers, therefore, in representing, in order to sell, these tiny differences between one player and another as excitingly new products to eager customers, themselves indoctrinated by the record review magazines, by radio and the press, and by popular musicology around performers: performer biographies, CD booklets, programme notes, and so on. In this way, critics, writers and broadcasters are equally implicated in the business of policing norms: they are paid to. So the business is organised around the nature of the products. Like Windows laptops, performers are almost identical, but marketed as excitingly new. (If you want to pursue the analogy, think of Apple as the Historically Informed Performance, the HIP, of musical performance, but it’s just the only other orthodoxy, and in it’s fact very little, and less and less, different.)

But more important than the marketing of normative performance is that side of the business that costs employers money, namely concerts and rehearsals. The industry is most profitable, the costs lowest, when there is least paid rehearsal. Rehearsal is as far as possible squeezed into unpaid hours, at home alone, so that when musicians have to be paid they are reproducing a known performance in front of a paying audience. Conformity is simply the most profitable model for the employer. The stunning trick that’s been pulled off is to have persuaded the worker to believe that this is both morally and artistically ideal. And in addition to get them to compete with one another, at their own expense, until only a handful (relatively speaking)—the approved virtuosi—are left doing all the best work. This is capitalism at its most ruthless, operating in artistic culture at its most moving.

And it’s that contradiction that I’d like now to address. We believe classical music constructs Utopias, in which all is miraculously harmonious in the best of all possible musical worlds. We enjoy performances achieved at an astonishingly high level of artistry which seem, by their very excellence, to validate the system and beliefs on which it rests. The very fact that, thinking we are representing the all-knowing composer-god, great experiences are produced, seems to prove that all is well, that we have found the key to experiencing composer-god’s mind; and that we must continue to represent it in just that way in order to experience his full glory. But in fact, all that wonderful music-making comes from the hard labour of people ruthlessly trained since childhood to make something apparently (or actually) emotionally moving, out of nothing more than notes in a score, filtered through a carefully controlled set of interpretative habits. A few, some middlemen, and a tiny number of corporations, then take the profits. So we have fabulous artistry generated from deep belief in a rich mythology, controlled and exploited by the meanest of motives.

You could say the same about Renaissance painting, or the Pharoahs’ tombs. But we don’t organise painting and architecture like that any more; only in classical music, the strictest disciplinary regime in the western world, outside prison (stricter even than armies, where you’ll find a lot more creative improvisation). Nonetheless, performers are contributing a huge amount to the music that results, because none of these performance norms is there in the scores. They are habits that have evolved, despite the best efforts of gatekeepers to prevent evolution, and they are habits of performance, not of composition. The habits the composer assumed are not encoded in the score. They are lost. The notes in the score are all there is. And they are just notes. It’s up to us, living performers and listeners, what kinds of experiences they generate. And, I am arguing, it should be up to us individually, not collectively.

*

So what follows? Two new principles and a host of benefits.

First, a performer should see the score as nothing more than a starting point for creativity. There is no valid ethical or historical reason against this. The notes left by the composer are there. You can change them if you want to, and they’ll still be there in other copies. You can interpret them in any way you like that generates powerful experiences for a listener (who may be just yourself). The dead composer doesn’t suffer, the notes can always be returned to and treated differently by others. You’re not drawing a moustache on the Mona Lisa. Nothing is irreparably damaged if you’re unsuccessful.

Second, we all have a moral obligation to performers, in return for all the years they’ve invested, to allow them to be creative and to personalise their reading of the notes, to find happiness in the joy of doing that, to avoid the stress that comes from fear of transgression [Biasutti & Concina 2014]. Performers would be far happier and healthier if they were freer to contribute. And we have no right to prevent that.

Let me list some of the benefits of this new approach.

Performers will be able to generate a much greater variety of musical experiences from scores, they will be able to use scores to comment on aspects of our own world, in just the way that theatre directors and actors are able to use new readings to enable old texts to tell us something new about our own situation.

Benefits will flow, from allowing and encouraging more performer innovation, not just for performers but also for listeners and for employers and for satellite professions, including commentators, indeed for everyone in and around the music business. Listeners will find concerts far less predictable, more like going to the theatre in fact, in order to hear a score mean something new; and it seems very likely that new audiences will be attracted to classical music, reversing its decline. That, of course, will generate new income for everyone else in the business.

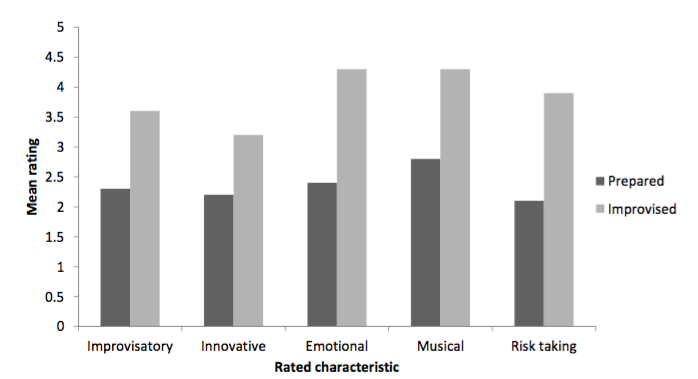

Dolan et al. (2013) The improvisatory approach. Music Performance Research 6:1-38

There’s an indication of how advantageous a new approach could be in a study by David Dolan, John Sloboda, and others, at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, in which an audience rated standard performances and performances including improvisation and unconventional expressivity. The results could not be clearer. On every measure the audience preferred the innovative performance (the grey bars in the chart above) by a huge margin. That’s a pretty strong economic case, never mind the artistic benefits.

Of course, teachers will have to learn to encourage creativity, not stifle it. That’s perhaps the biggest change of all. But once they’re discovered how to do it as performers, they’ll begin to experience and understand the delight that it can bring, and they’ll want to share that with their pupils. From which you’ll understand why I believe this revolution can only be made by young professional performers like those who made this production of ‘Dido’. With diminishing opportunities to make a living from the present system, a whole career ahead of them, and enough technique, and in the best conservatoires an increasingly imaginative education, only young professionals have the tools and the incentive to introduce radical change.

Examination systems will have to change to incorporate credit for creativity. (Incidentally we’ve already done this with our performance regulations here at King’s, and we’ve introduced a final-year course that fosters innovation.) Agents will have to select performers to promote on the basis of their imaginations as well as their reliability and sexiness, which shamefully is often a significant consideration now. Critics will have to learn how to respond to and how to value readings of scores unlike anything they’ve heard before (and you can see what a tough battle that’s going to be). And everyone will have to stop asking whether a performance is correct or not. There is no correct or incorrect, because there are no valid criteria for evaluating performances other than the extent to which they move or excite or interest or fascinate us as we listen.

One further point, a vital one: we learned from HIP, which over time and with much experimentation created a new performance style, that the only way other performers change their habits is by hearing convincing performances in the new manner. It’s no good just talking about changes that ought to be made. We have to hear the results before anyone else will be persuaded.

Which brings us to ‘Dido & Belinda’.

We had two aims here; first the more general aim of allowing and encouraging performer creativity; secondly to narrow the gap that bedevils opera between the attitudes of the stage and music directors. This relationship can in theory take any of these four forms (not excluding others), in each of which the notion of ‘matching’ stage and music interpretation imagines a situation in which both aim to communicate the same understanding of what the notes and words might mean in a particular production.

- The staging tries to match the musical interpretation. This would be interesting to try to achieve. Where would you set a production that did that? In modern dress? Or in the 1950s perhaps, where current musical performance style became an international norm and whose values (of regularity, sobriety, good manners) it could be said to represent? Certainly it would require to be set in a socially narrow context, among the relatively affluent upper-middle class white westerners who make up most of the audience and most of the performers. Inevitably, productions would all be very much the same, but that in itself tells us something about the way we currently make music from these scores.

- The music tries to match the staging. This is very hard for musicians to conceive at the moment. How do you perform notes so that they sound Nazi, for example? But it’s a problem that’s not as insoluble as it seems. We’ve just not been able to try it yet because of all the political-moral constraints placed on (and accepted by) musicians: the obligation to continue to play the notes according to current norms.

- The music and staging just ignore each other. That’s what happens at the moment. How is that good? What’s sensible about it, artistically? It’s only because music, well-performed, can be so overpowering that this blithe indifference works at all. We go along with the music, and hope that the staging seems carried along with it. Or we just shut our eyes.

- Both directors—stage and music—work together on an interpretation of story, words and notes, and try to get them to work as one, mutually adjusting their vision to one another’s until they have something that makes coherent sense in both domains.

In ‘Dido & Belinda’ we’ve taken a combination of the second and fourth options. In our production both stage and music director are aiming to allow the ‘Dido & Aeneas’ text and notation to shed some light on the same set of current social concerns, namely the limiting of gender choice (which can stand as a symbol for everything I’ve been saying about the limitations imposed on musical performance), and the resulting conflict between feeling and behaviour, and appearance and reality.

We began by workshopping alternative performances of Dido’s lament, since that inevitably is the focal point of any performance in the minds of anyone who knows the piece. At this stage it seemed to work best as a love duet for Dido and Belinda, sinuously sensual, with the final duet of ‘Poppea’ in mind as one possible model. Knowing now that other musical readings were possible, and intrigued by how the opera might work if Dido and Belinda were the lovers, and Aeneas an inconvenient obstacle, we then developed a new reading of the complete plot. It’s a commonplace of ‘Dido’ criticism that Aeneas is unconvincing both as lover and beloved. Dido and Belinda are obviously much closer to each other than Dido is to Aeneas, and Belinda is there with Dido at all the most intimate moments. If there is a loving relationship in ‘Dido’ it’s more plausibly theirs, one might think. In that case it’s easy to imagine why Aeneas finds himself in the wrong place at the wrong time, and why they should be so keen (and Dido really is keen) to get rid of him. (‘I’ll stay’ – ‘no, no.’)

Around that core observation the other details fall into place. Aeneas, whose main enthusiasm is for the massive boar he’s killed and that’s bending his spear, is an narcissistic oaf, and Dido’s extravagant praise of his manliness in the first act (‘when could so much virtue spring? What storms, what battles did he sing?’) becomes bitingly sarcastic. In the second and third acts Belinda and Dido conspire with the witches to get rid of Aeneas by conjuring up a storm and having Belinda dress up as a messenger from the gods. At the same time, they are hemmed in by their own retinue whose values are entirely conventional, who expect her to marry a macho warrior, and among whom it’s impossible for Dido and Belinda to live openly as a couple. And so, in the famous lament in the final act, Dido and Belinda are free to construct a fake suicide note, and leave it behind for the chorus to discover, while they elope and, let’s assume, live happily ever after.

With that as a guide, the conductor Leo Geyer and the musicians took over, and, together with Ella Marchment as director and Simeon John-Wake as movement director, they developed their own reading of the score in order to tell that same story as persuasively as possible. It’s my own belief that with enough practice, perhaps several years’ worth, it’s possible to do this without changing the notes Purcell left: that there’s enough space, in the notional world of possible persuasive performances, for a score to mean radically different things simply by the way the notes are played. As we didn’t, however, have unlimited funds for rehearsal (though with wonderfully generous funding, even so, from King’s College London) Leo next constructed a score in which he imagined a complete reading that fleshed out our original outline, making some modest changes to the score as a way of testing what might be possible (including some reordering of numbers, reassigning (as we always envisaged) some passages between characters, some changes of harmonisation and rhythmicisation). That’s absolutely a right we have with any score, in my view, given the points made above about obligations to composers, musicians and audiences. So when you listen to the video you’ll hear some compositional differences here and there.

Then, as an essential part of the rehearsal process, the production team and the musicians experimented with different readings of key scenes, some of which we later performed as alternatives after each performance. In those post-performance sessions we asked the audience and performers to interact, and for the audience to suggest further possibilities which the musicians might try out. That in turn could be fed back into the next night’s performance. In other words, we were not just offering a new way of hearing this score, but also a new attitude to what a score can do and to what it’s for. And we wanted to explore that with our audiences, not perform it at them.

*

In conclusion, I want to step back and look at these questions on a much wider stage. The United Nations’ guidance on Human Rights pertaining to the right to artistic freedom includes:

“the right of all persons to freely experience and contribute to artistic expressions and creations, through individual or joint practice, to have access to and enjoy the arts, and to disseminate their expressions and creations.”

And that is exactly what we are doing. It seems to us that any claim one might make for Western classical music to be exempt on grounds of artistic quality or ontology is bogus, concerned with protecting privilege and not with artistic quality which is easily achievable in myriad other ways, much to be benefit of musicians’ wellbeing psychologically, socially and economically.

And so for us ‘Dido & Belinda’ is a first, tentative, no doubt only partly successful step towards a radically new situation in which professional musicians have the agency their astonishing abilities deserve, and indeed that their human rights require. In the long run I think we’ll all benefit, difficult as it may be at first for all to accept!

I can’t end without expressing my heartfelt thanks to King’s College London for enabling this production. It’s not easy, in these times of ever-increasing government scrutiny and therefore conformist pressure, to put so many resources into something so experimental, but that is exactly what universities should be for: to generate and test ideas that may in the long run benefit society but that society is not yet perhaps quite ready to imagine and fund. Warmest thanks to King’s, then, and thanks to you for reading.