24 Reinterpreting opera

24.4 ‘Dido & Belinda’: what the audiences thought

Are audiences really ready for this kind of work? I’ve argued earlier that there is real potential here to attract much larger and more diverse audiences, simply through making performances that are not known in advance and that are able to interact with current concerns of the wider field of art, with social concerns, and that provide themes for debate by people with cultural interests far beyond the narrow world of current WCM. But is that borne out by audience responses to ‘Dido & Belinda’?

Audiences too have been taught to share the standard ideology and to believe that the performances they encounter in concert and on record represent the composer’s intentions and do it as well as it can possibly be done. How would they react to this very different take on ‘Dido & Aeneas’?

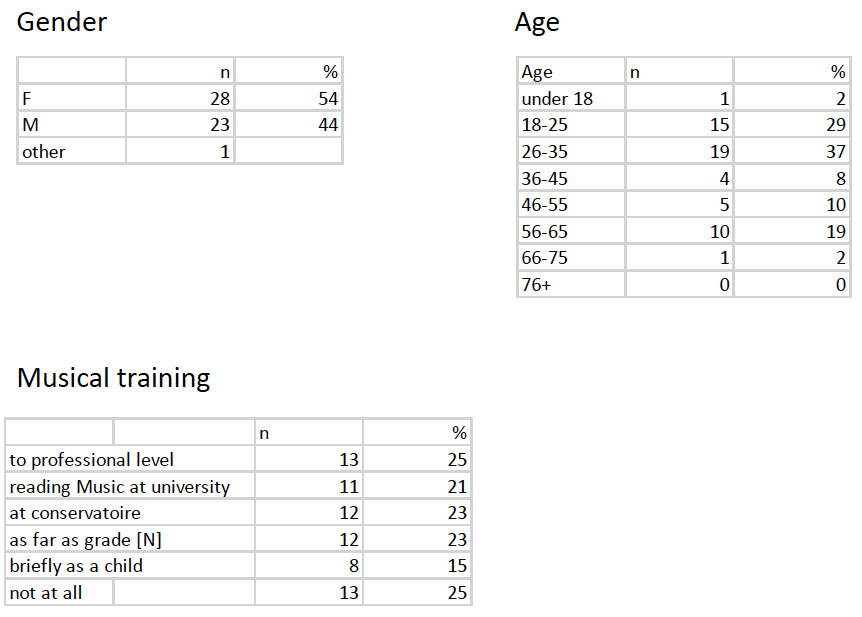

We placed an audience questionnaire on every seat at each performance and received 52 responses, about a third of those who attended. Two-thirds of these were aged 18-35 and most of the rest 46-65.

Judging by their detailed responses the younger ones were mainly friends and colleagues of the performers—25% or all respondents were professional musicians, another 16% had studied music at conservatoire or university but were not professionals, which is a pretty high proportion for an audience—while the older group probably included parents and family. So it may not be surprising that comments were overwhelmingly favourable. But I’ll try to tease out more nuance as we look at the results.

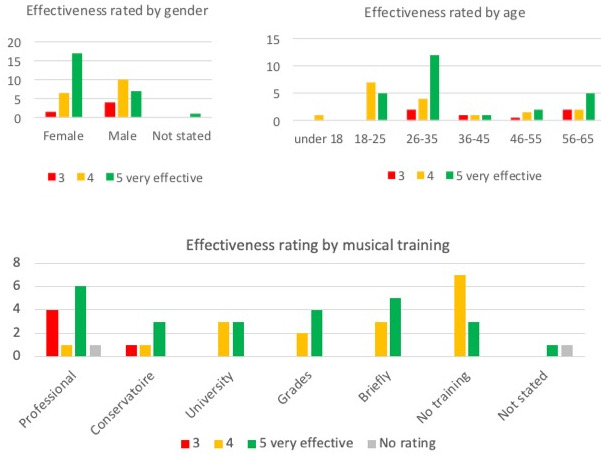

Perhaps not surprisingly, given the reworking of the plot empowering the women, women were much more likely to rate the opera ‘very effective’ than men, as were those in the 18-35 age bracket (who are exactly those whom the project aims to reach since they have most to gain from new performance options):

Opinions were most divided among professional musicians, as one might expect given the challenge to the values in which they were trained. On the other hand, professionals also provided the largest number of 5s (the highest rating). Those with less musical training mostly scored effectiveness at 5; while those with none, mostly at 4; which I assume is because for them it was just another opera, whereas those with some training were aware of the implications and were nonetheless convinced.

Among the professionals, a male in the 36-45 bracket commented that ‘I felt no need for this tampering’ and they felt ‘angry at times’. A younger woman found it ‘extremely effective … revitalising, engaging, exciting, interesting, rejuvenating, refreshing’. A male of the same age found it ‘truly enjoyable’ and left convinced that ‘Opera is 100% the key to unlocking the door which will let us escape our current aesthetic prison we find ourselves in.’ And I think there’s truth in that, in that it’s simply easier to wrap up as dramatically necessary than with a string quartet, for example. (Or indeed the Moonlight sonata.)

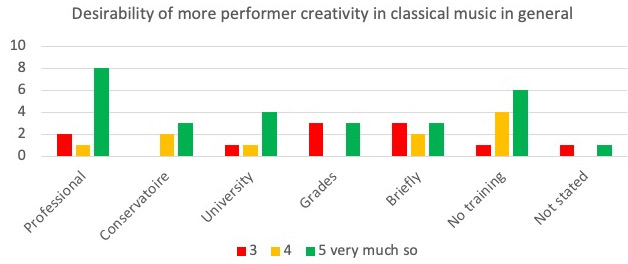

I asked some of the same questions that I asked the performers. 57% think now, in the light of this experience, that classical music performances would benefit ‘very much’ from more performer creativity, with professional musicians among the audience much the clearest that they would like to hear more creative freedom.

Among comments on reinterpreting the story there were four objections to the feminist or lesbian themes, three of those from older men, the fourth from an older woman; but a lot of strong support from younger and women audience members.

On reinterpreting the score, detailed comments were more varied. Several of the standard tropes were reproduced:

Music is for me sacred. It’s the composer who decides how to make it sound. (Male, 18-25, musical training as far as grade exams)

i.e. the belief in composer as god. And:

it struck me that he perhaps meant this score to be highly adaptable (M, 56-65, beginner)

i.e. the composer’s intention as authorisation.

Others were more discriminating:

Musical transformations / Intriguing, sometimes unconvincing, others brilliant. (M, 56-65, university music training)

These weren’t always too integrated and thought out into dramatic concept, but when they were they worked. (M, 26-35, professional)

Quite a few would have liked us to go further, which I must say did surprise me:

Un-notated inflections from musicians in pit [f]elt appropriate … could probably have gone a little further (M, 46-55, university)

Freer vocal performances including improvised (?) ornamentation. … I think the singers could have gone even further. (M, 46-55, university)

Both direction and musical re-interpretation successfully translated. 21st century re-imagining could’ve possibly extended. (M, 26-35, professional)

The integration of musical and stage direction was noted by a professional:

Orchestra seemed to have more agency as a musical entity than I am used to hearing in opera. It seemed more integrated with the stage action (Female, 26-35, professional)

and it was good to know that that came across.

There were a great many general comments, far too wide a range to illustrate, but they included the man quoted earlier who felt ‘angry at times’:

I definitely prefer a ‘proper’ historically informed performance. Well, I am a musician and this evening won’t change what I do and how I do it. (M, 36-45, professional)

But also this from a younger professional musician which illustrates the key point that no damage is done to an artwork by this kind of performance: the sources remain, they’re unaltered and available to anyone to read in other ways.

You didn’t improve Purcell. And that is *exactly* what I loved: by virtue of the fact I think you weren’t trying to create the ‘quintessential’ performance. But it was different. And really successful. And in a country where 100 other Didos are being staged this year, the opportunity to experience a unique version is really wonderful. (M, 26-35, professional)

But I was particularly interested in the general comments from people without musical training, because I want to get a sense of whether, as I hypothesise, a much wider range of performances could increase the audience for classical music. Here’s a selection covering the age range:

It was loads of fun to watch. And far more effective than the Purcell staging at the Barbican on Monday. (F, 56-65, no musical training)

I think the production would work very well as a gateway to audiences who would normally be reluctant to see operas. (gender not stated, 46-55, nmt)

The experience has made me realise that opera/classical music can be interpreted in ways that make performances feel more relevant and engaging, especially for an audience not well-versed in classical music. (F, 18-25, nmt)

… makes me want to go see more events like it. (M, 26-35, nmt)

As a first exposure to opera it was a thoroughly enlightening and engrossing introduction. (M, 26-35, nmt)

Of course this is not a representative sample for the more diverse audience I think we could reach, but it is pointing in a very encouraging direction. A couple of final comments:

It was an inspiring evening that proved much more radical interventions in scores can be vitalising forces, not vandalising ones. (M, 46-55, university)

And:

As for classical music in general, this evening didn’t and couldn’t address the question of what ‘reformed’ performances and presentation of, say, Beethoven string quartets or piano sonatas, or Boulez’s La Marteau sans maître, might feel and sound like. Still, food for thought and for future experiments. (M, 56-65, childhood lessons)

And with that I completely agree. It’s exactly what the experiments with instrumental scores here at challengingperformance.com aim to explore (see the drop-down list from ‘Interviews and Recordings’ in the menu at the top of this page).

I believe this is enough to provide some support for my claims that much more varied readings of canonical scores are possible, musically and in principle, and produce results that are thought-provoking, engaging, persuasive; that musicians find this kind of work refreshing and rewarding; and that they have the imagination and skills already to work this way, if only the occasions are provided and they feel empowered and safe to be creative.

I hope, also, that these data suggest to you that the audiences that we can already begin to see emerging with new venues and new forms of presentation are likely to be sympathetic to these much more open kinds of interactions with texts from the past. There are real possibilities here for generating new work and new audiences for adventurous young musicians. The problem is to get the profession to enable, not to block these sorts of approaches. And only successful examples will achieve that, examples that people want to emulate and improve upon. Musicologists just talking about it aren’t going to make the slightest difference: people have to get out there and do it!

Continue to Chapter 25: Speaking of contemporary concerns

Or if you’ve not done so, watch ‘Dido & Belinda’ now:

[NB the performance begins at 8:00 minutes, so feel free to skip the introductory interview with Daniel Leech-Wilkinson, introducing the concept for YouTube viewers, which you won’t need if you’ve read this far!]

Detailed audience and performer feedback (links to PDFs)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.