24 Reinterpreting opera

24.3 ‘Dido & Belinda’: what the performers thought

Why this production? In the first place, of course, I wanted to show that a persuasive production can do things I’ve been suggesting in this book: in this example leave the score largely intact, and yet enable it to mean more to a contemporary audience than a normative performance; be funny and touching and dramatic and beautiful, and yet say something to a youngish audience today.

But I also wanted to know how performers would find the experience, shocking or infuriating or engaging; and I wanted to know how audiences would react, depending on their previous experience and expectations. And so I used the performances to run two questionnaires, one for performers, one for audience. The results are provided in detail in the ‘Dido & Belinda’ section of the Challenging Performance website. I’d like to share a smaller and more readable selection of the results here, though, because I think they do suggest that this may be a way to go if we want to enlarge the options for young performers in the future. Which is the whole purpose of this book.

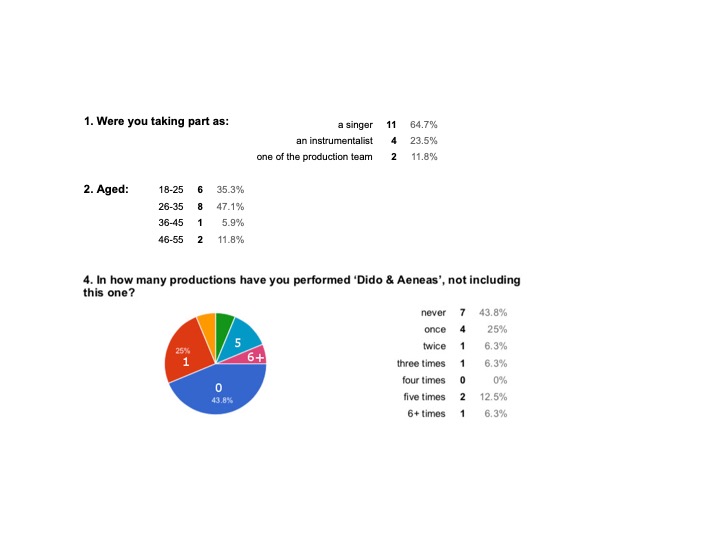

As well as a couple of members of the production team, I got fifteen performer responses which amounts to 50%, a fair sample. Two thirds were singers. Most were young, so people in the process of forming careers. Most were experienced opera performers, some of whom knew ‘Dido & Aeneas’ very well:

I asked them why they agreed to take part. Seven were specifically interested in the chance to do something different. For example,

I was really interested in what direction the opera would be taken, and how far it would go (instrumentalist)

And some had more down-to-earth reasons:

At that point, I was still only interested in the money (singer)

though later this performer did find the process very engaging.

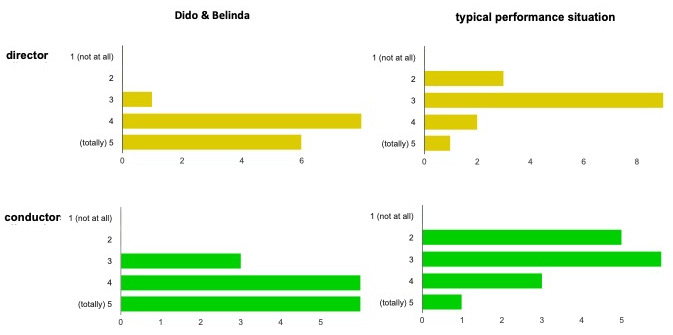

I asked them how creative they felt they themselves were allowed to be by the director and the conductor, and how that compared to their experience in a typical performance situation:

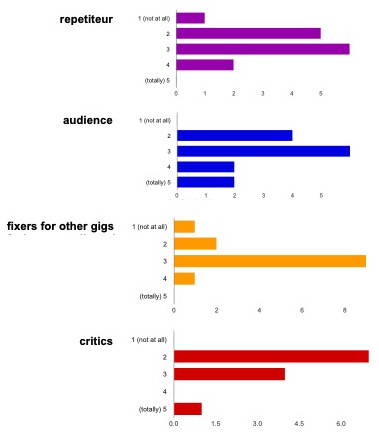

I also asked how creative they usually felt allowed to be by others including repetiteur, audience, fixers for subsequent gigs, and critics:

And that result ties in strongly with the research reported in Chapter 9.2 on the strength of hostility among critics.

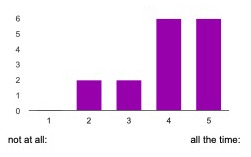

I asked how much, in a typical performance situation, they worry about performing in correct style:

This is an extraordinarily telling result, confirming everything we saw in Chapter 14 about the impact of policing on musicians’ health.

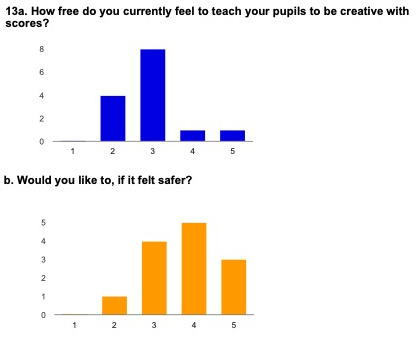

I asked about their own teaching, hearing a clear preference for teaching more creativity than they feel they can:

And I asked them what stops them; and here I got interestingly conflicted responses:

Expectations

…adjudicators, mark schemes etc

Feeling that there is a ‘correct’ way something should be interpreted and that by doing something different I am somehow doing a disservice to the music or at risk of being criticised for not doing it in the ‘correct’ way.

And from that anxiety to:

I am quite a firm believer of performing what is written and performing what is believed to be the composers’ intentions, stylistically and musically.

In other words, their gut response, reflected in the charts, was to want to be able to teach more creativity, but when asked for their thoughts there was a tendency to revert towards the standard ideology.

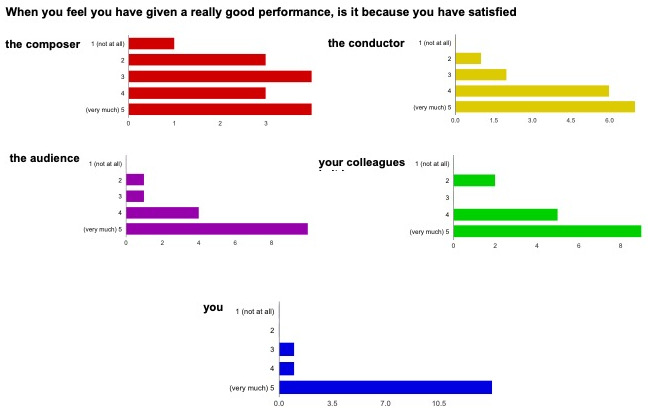

I then asked whose pleasure most justified a feeling that they’d given a really good performance. The point of this question was to find out whether their respect for tradition really was the main value in which they believe. And here the results told a slightly different story, suggesting that the opinion of contemporaries is far more immediately important (though ‘you’, at the bottom, is obviously complex because it includes elements of the others; and needless to say the opinion of others is the product of the ideology):

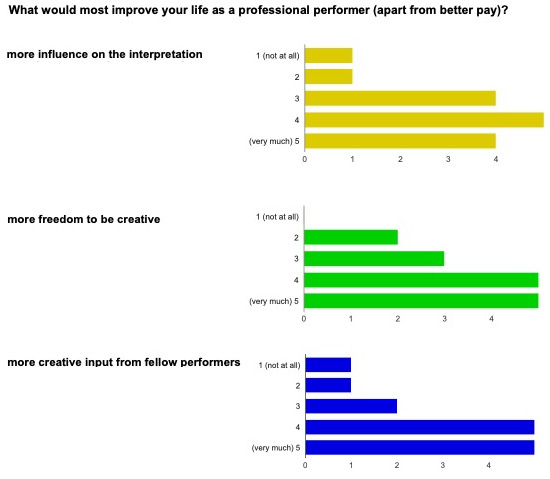

From here I went on to ask what would most improve their lives as professional performers. The strongest trends were for more influence on the interpretation, more freedom to be creative, and more creative input from fellow performers:

I thought that was interesting, emphasising the extent to which encouragement from peers would provide support; and this in turn confirms the suspicion that if enough performers started to work together on these sorts of approaches that itself would provide a safer and more productive environment in which to be creative.

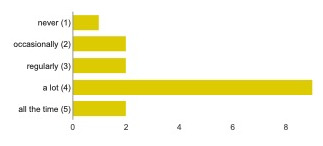

Very clear support comes from their answers to, ‘Would you like to work like this with other well-known scores?’:

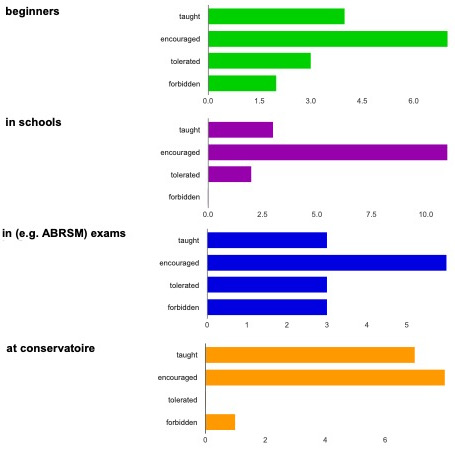

I asked at what stage in music education they’d like to see this approach to performing classical scores be taken, and how much. There was surprising enthusiasm, I felt, for encouraging young players to be more creative; more mixed feelings about exams; and strong support for teaching it at conservatoire:

I imagine that this ties in with the still widespread belief, which I’ve observed in other data, that you need to learn to interpret ‘correctly’ before you (to quote a teacher) “mess about” with the score. That sense that there is an original, and that we know what it’s like, and that reproducing it is our first duty, is still overwhelmingly strong, since it’s been repeated endlessly since first lessons. But that being so, the strong support, after the experience of performing in ‘Dido & Belinda’, for teaching similar approaches in conservatoire is still heartening, I think.

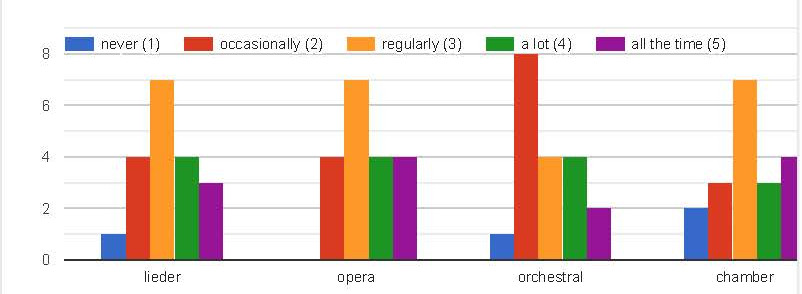

I then asked about the repertoires in which they’d like to see this approach taken. The strongest support was for song and opera, and interestingly the least support for orchestral music.

The idea of an orchestra doing something different seems hardest to contemplate, perhaps because it’s so antithetical to orchestral musicians’ everyday experience. As one performer commented:

It’s all a bit like a battery farm in orchestras these days. …any attempt to discuss the musical interpretation of a piece … would be professional suicide. (instrumentalist)

I asked what they least and most enjoyed about working on this production. Least enjoyed were rehearsal constraints:

By the end of the rehearsal process I felt like the performers were just beginning to feel comfortable enough to be really creative and take risks

Most enjoyed were:

Creative freedom – lifechanging eyeopening experience.

I really enjoyed the fact that everyone, singers and instrumentalists alike, were encouraged to come up with their own ideas.

The opportunity to be involved in something innovative and imaginative in an industry which is brimming with unoriginal productions. (production team member)

The way the show developed over the three nights - changing things and watching the audiences’ reactions. (singer)

And in fact in a further, matinee performance for covers, to my total surprise (as Dramaturg) the witches slit Dido’s throat, so that there was no happy ever after. I was appalled but I also loved the fact that they felt free to do it. So this one’s interesting:

Trusting my colleagues to get a positive and beautiful response from everyone else on stage when we all try something new. (singer)

I asked what they thought they could transfer from this production to their normal professional music-making, and here the responses were most consistent of all:

[not] to take everything as gospel.

Don’t be afraid.

be braver.

And

I think a greater sense of “what if….?” when approaching my music making, rather than singing a standardised version by default.

And actually for me that ‘what if?’ question is one of the most important. ‘What else can these notes do?’ is the question I ask constantly when working with performers because it addresses our relationship with the score and our sense of what potential the composer has initiated. It’s obvious from the way, and the extent, that performance has changed that every score can be persuasive in many more ways than are normative at any one place and time. The composer can’t envisage that. Referring back to the composer’s intentions is to seek to evade most of that potential and, don’t let’s forget, also to invalidate every performance any of us has ever made or heard of any piece older than ourselves. Performances like this ‘Dido’ bypass these sorts of nonsensical but ideologically enforced beliefs.

Nothing made that clearer here than the responses of one of the singers, the one who insisted that they were ‘a firm believer of performing what is written and performing what is believed to be the composers’ intentions’. When I asked about prior expectations of working on this production they’d selected ‘I expected a difficult or unpleasant experience’, and when I asked what would most improve their life as a professional performer they said, ‘More detailed instructions in the score.’ And yet at the end of this long questionnaire, when I asked if there was anything else to add, they wrote:

Thank you so much for giving me the opportunity to perform this wonderful re-imagining of Purcell’s work! I honestly didn’t think I would enjoy it as much as I have! I am overjoyed that I got to be a part of this amazing company and really relished every rehearsal. Thank you again!

There is huge potential here for a more fulfilling professional life.

Continue to 24.4 ‘”Dido & Belinda”: what the audience thought’

Detailed audience and performer feedback (links to PDFs)

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.