Anna Scott

Pianist and researcher Anna Scott uses early recordings to inspire startlingly original interpretations of Brahms.

Anna Scott is a convert. She admits that:

Like most mainstream performers, and probably also historically informed ones too, I believed that what I was doing when I played Brahms was some combination of faithfulness – whether it was to Brahms, or his scores, or evidence about how he wanted his music played – and creativity.

Her outlook was transformed when, for a 2006 graduate class assignment, she found extant recordings of Brahms pieces performed by his contemporaries.

The performers on these recordings had all been former pupils of musician and composer Clara Schumann, and were close friends, colleagues, as well as informal pupils, of Johannes Brahms himself. What was surprising was that this group of performers around the living Brahms were playing in ways that contravene our own contemporary criteria for ‘good’ Brahms playing.

The early audio recordings of Brahms caused a two-fold shift in Anna’s perspective. At one level, the composer she thought she knew well had changed. She felt ‘shocked’ to hear familiar scores rendered in unfamiliar ways by people who actually knew Brahms personally. Her idea of what it meant to be a performer also changed. Anna had always thought she exercised ‘creative agency’; a ‘right to play in the ways that I like’, even if to some degree her choices reflected ‘agreed upon boundaries of taste and style and technique.’

These recordings were so unique, however, that the interpretations she would previously have counted as ‘creative’ appeared only to be a cautious sliver of the myriad ways that Brahms could sound. Their existence called into question our prevailing notions of older repertoire for which there are no extant recordings. The way Brahmsian performance was critiqued, conceptualised, listened to in the 21st century was ‘neither as creative nor as historical’ as most people assume.

It wasn’t immediately obvious what made these performances sound so different.

Recordings of Brahms’ work by Hungarian pianist Ilona Eibenschütz challenge the aesthetic criteria by which we evaluate Brahms performances today

You can incorporate some of these 19th-century techniques in your playing [..] rolling chords [..] right hand and left hand apart..[even] improvisation, without really disturbing the fundamental pillars of what Brahms’s pieces are meant to be like today.

Rather, their distinctive quality lay in features that subtly pervaded the pieces’ entire form.

I was much more interested in the really big, extreme ways that their performances differed from ours…really consciously working against structure as is notated…this very lopsided and hurried approach to time. When you combine all of these things together, then you start to make performances that sound like Brahms and his students.

The old recordings ignored major structural divisions in the pieces that her modern ears were used to hearing. Anna found that in order to copy exactly how Ilona Eibenschütz or Adelina de Lara played Brahms, she had to consciously force herself to break the habits thought to belong to a supreme Brahms interpreter of today.

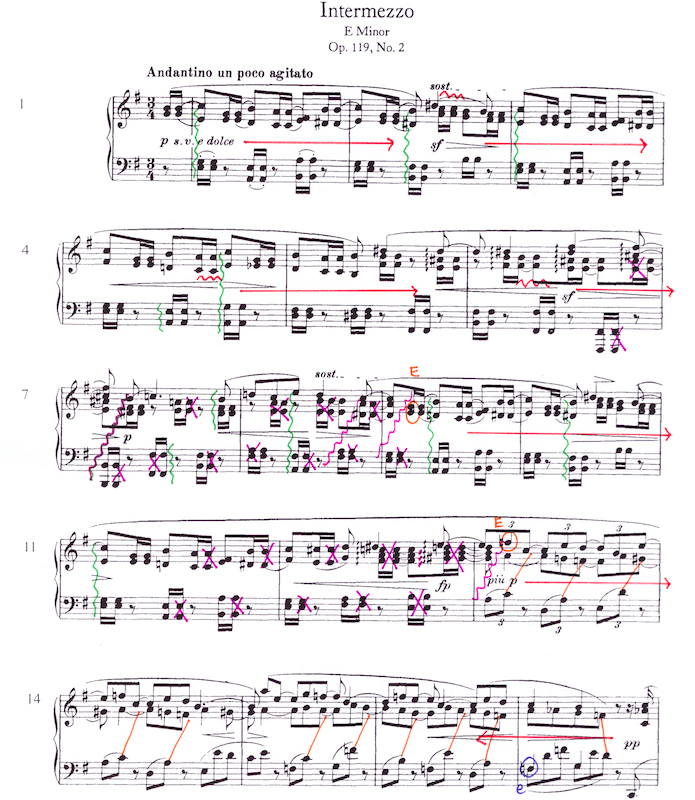

Anna Scott’s exact copy of Intermezzo in E Minor, Op. 119 No. 2, as performed by Ilona Eibenschütz on a 1952 recording

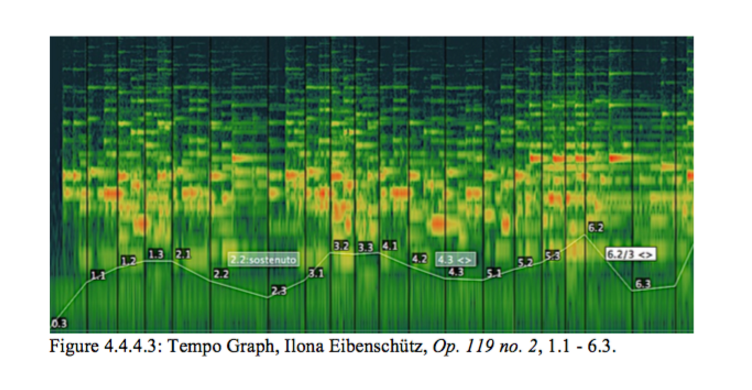

Anna’s creative process starts off with a painstaking copying process. Above is an exact copy of a 1952 performance by Ilona Eibenshütz. Reproducing this recording note for note required not only close listening, repetition, and a large dose of trial and error, but more precise aids as well. Below are spectrographic tempo graphs of the recordings which provided Anna with a magnified visual representation of musical events in them.

This allowed Anna to deconstruct exactly what made these playing styles of the circle around Brahms sound so individual to modern ears. As Anna subjected the recordings to these auditory and visual methods of analysis, she would mark up pages of her score:

Anna’s performance practices could therefore be described as a kind of musical method acting. She inhabits the technical range of these first Brahms performers through deep structural analysis and exacting replication. This process of listening and playing allows Anna eventually to internalise the techniques so that she can render scores in the style of Brahms’s contemporaries at will.

Alongside her work on Brahms’s circle, Anna has continued to play the composer’s work in a more familiar, mainstream style. But her mainstream playing has also been informed by her creative experiments insofar as they have heightened her awareness of decisions she makes as she plays, in a way that she could not have accessed before her encounter with historical recordings. By retrieving older styles of performance, Anna has gained a unique critical vantage point from which to examine how performance involves continual creative choices and commitments to a certain idea of a composer and their work – even if they are not consciously acknowledged as such by performers, critics or audiences.

Interpretation of Brahms’s Intermezzo in B Minor, Op. 119 No. 1, in the style of Eibenschütz and de Lara.

One way this recording differs from standard 21st-century interpretations is its use of dislocation. This was a once commonly-used technique which is all but forgotten in modern performance. It involves detaching a melody (normally in the right hand) from its accompaniment (normally in the left hand). The technique alters the temporality of the music, ‘shifting’ the moment a particular part of the melody is played in relation to other sounds. To the listener, this will sound like subtle delays or lags in the musical flow.

Aside from dislocation, more fundamental and structural differences exist between modern performance styles and how Anna plays here. Eibenschütz, whose playing was highly admired by Brahms himself, combines dislocation and hair-raising acceleration to blur the boundaries of both the large, sweeping structures and the smaller ones which together constitute Op. 119 no. 2. Anna has recreated this in Op. 119 no. 1 by similarly disregarding boundaries modern players would normally emphasise.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.