7 Teaching

7.7 Micro schools and their discontents

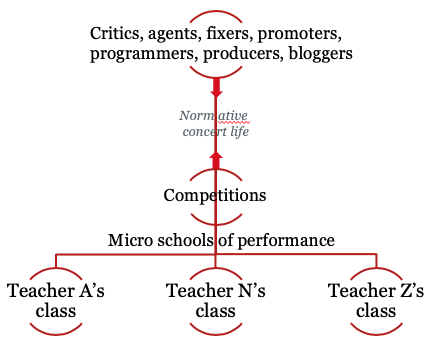

Another model of WCM gatekeeping may help to place competitions in relation to teaching and other kinds of performance policing. (And there is a more detailed version in 7.7a.)

Here, normative concert life is squeezed between the pressures applied by the widespread gatekeeping in the profession (critics, agents etc)—which is never silent about anyone with a public profile, while anyone without one yearns for the notice—and the long preparations through teaching and competition. In line with Izabela Wagner’s findings, and for that matter with anyone’s experience of high-level training and career-formation, teaching is modelled as consisting of micro schools. Here the individual teachers—the ‘masters’ or ‘professors’ with whom students seek to study in order to benefit not just from their teaching but also, crucially, from the patronage and contacts—sell themselves, to those students with greatest potential to be led and to succeed, as the only teacher who can guarantee them a career, playing the correct way, benefitting from the best address book. The micro schools represent musical dynasties (Wagner 2015, 61) through which teachers both show their knowledge (122) and seek (though, thanks to style evolution, never succeed) in ensuring the survival of their interpretations, their own musical genes.

The extent to which identity is bound up in these slightly differing views is illustrated by one of my questionnaire participants:

I can remember playing the Rhapsody from Brahms op. 119 to my teacher (…), after attending a summer course with a different pianist (…). The latter had suggested that just before the recapitulation I bring out more the inner voices (with detailed reasoning based on score analyses of legato marks and note lengths), creating effects that have rarely been used by other pianists. My teacher felt it was all too thought out and irrelevant, an unnecessary complication, dismissing completely my enjoyment of that approach. … since that day the relationship with him started to fade. (Pianist, 30-9)

To have a different musical response is to reject not just your teacher’s preference but the self whom that preference sounds. The following is a selection of similar comments from the questionnaire responses which give a sense of how common this is, of just how closely teachers identify their readings with themselves, and of how unable they seem to be to recognise a student’s right to a view of their own.

I think most teachers I have had in any instance (lesson or masterclass or coaching) have in the end been about trying to get me to play their ideas, rather than trying to teach me to play my ideas better. (Violinist, 30-9)

I was shouted at by one of the jury members of a German competition for playing Bach too slow, with pedal and with too much contrast[, his] only argument being that “you cannot do that”. And in order to humiliate me about it more would develop on the poor standard of London conservatoire[s] since students merely had to pay to get in. (Pianist, 22-29)

… final exam. Panel of conservatoire, for interpretation I had to follow… my professor’s interpretation. … I failed my exam when I know I did not play badly…. Didn’t agree with interpretation myself but had to follow… [M]y own professor felt angry with me because I was meant to be the star student to represent them. I was caught in the middle of this political thing because my professor was new. … [P]rofessor never spoke to me again because the comment I received said the interpretation was not authentic. (Cellist, 30-9)

One of the judges … devoted all of her critique of my aria to telling me how inappropriate it was to add notes that the composer hadn’t intended, and how I would have known better if only I had studied at the Mozarteum, as she had. Ironically, I HAD studied with a teacher at the Mozarteum the previous summer, and it was that very teacher who encouraged me to ornament that cadence in the aria! (Singer, 30-9)

This kind of behaviour arises inevitably from a system in which all are competing to produce the most persuasive version of a product that is already comprehensively standardised. Competition focuses on the tiniest details, differences far smaller than could easily be accommodated even within the current practice, never mind stepping outside the norm. The squabbling arises, nonetheless, because of the false claims we examined in Chapter 6, all tending towards the assumption that there must be one reading that is better than all the others. I think it must be clear by now that there isn’t, and that these scores can make persuasive music in an enormous variety of ways according to personal, local and period tastes. To build one’s authority as a teacher around the claim that one knows how the music should go is only to advertise one’s failure to handle the variety of past and possible approaches to performing WCM.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.